How To Tell If A Fossil Hominid Was Bipedal

By Jim R. McClanahan

By Jim R. McClanahan

Human evolution is obviously one of the most important aspects of human history, so I've decided to post information on how to tell whether or not a fossil hominid was bipedal. It's not as difficult as it sounds. The following list is by no means meant to be comprehensive. Just look upon it as a primer.

The first place to look is the head. All vertebrates have a hole in the skull through which the spinal cord connects with the brain. This hole is known as the Foramen Magnum ("Big whole")--my professor actually used a condom joke to explain the name. The foramen magnum in apes is positioned on the back of the skull due to their bent over posture. This of course goes back to our time in the trees when we had to look forward while running quadrupedally along the limbs. Humans have a foramen magnum that is position under the skull due to our upright posture. Next, the muscle attachment points on the occipital protuberance are positioned further back on the skull of an ape, while the attachment points are positioned under the skull in humans. If a fossil has a foramen magnum and muscle attachment points more under the skull, then it was most likely bipedal.

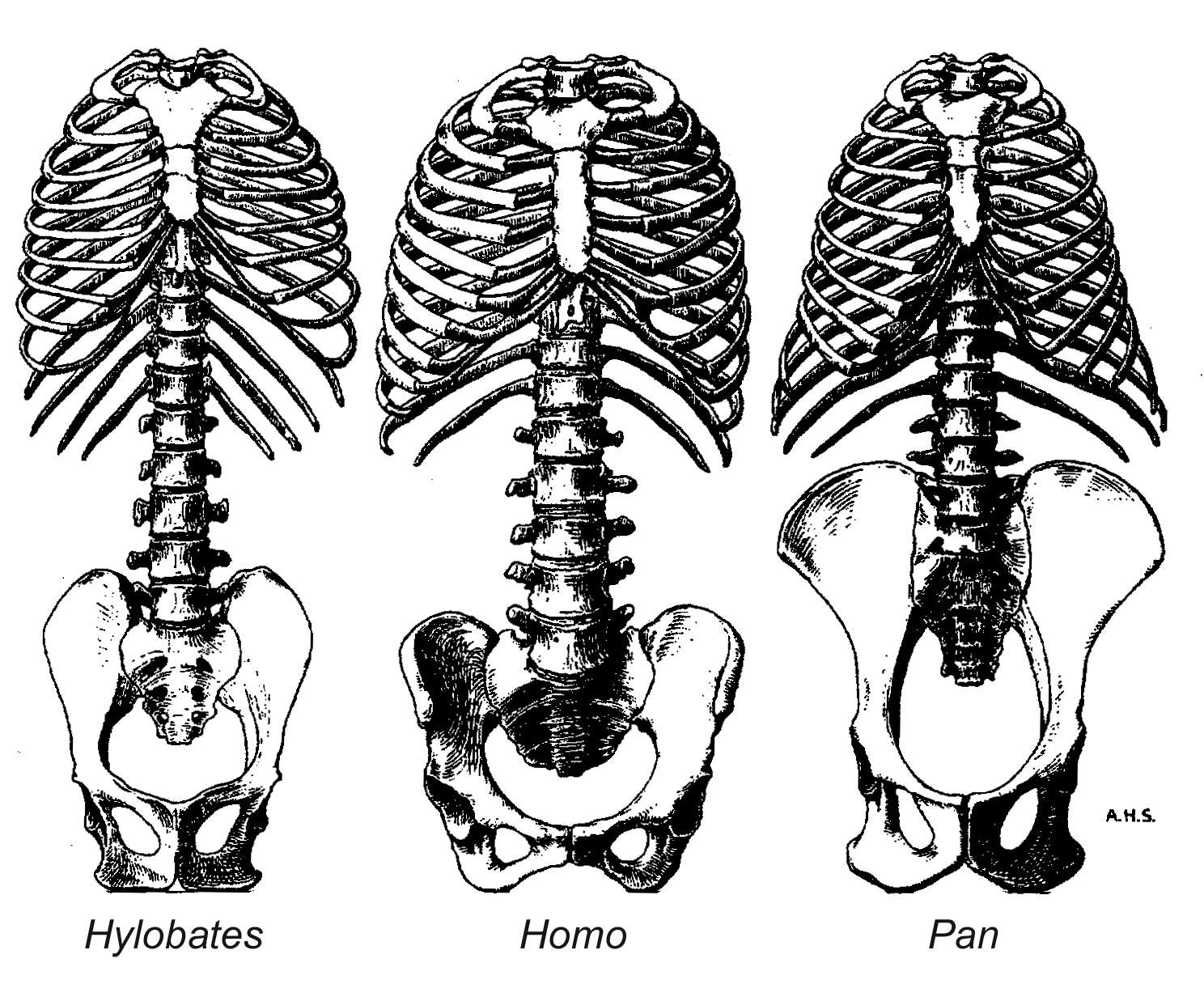

The second place to look is the spine. Apes have a C-shaped spine. This shifts their center of gravity towards the upper part of their body. This is one reason why they look so funny trying to walk bipedally. Humans have an S-shaped spine, which shifts the center of gravity more towards the waist.

Also, in comparison to apes, humans have bigger vertebrae to support all of our weight. If a fossil has more of an S-shape and robust vertebrae, it was most likely bipedal.

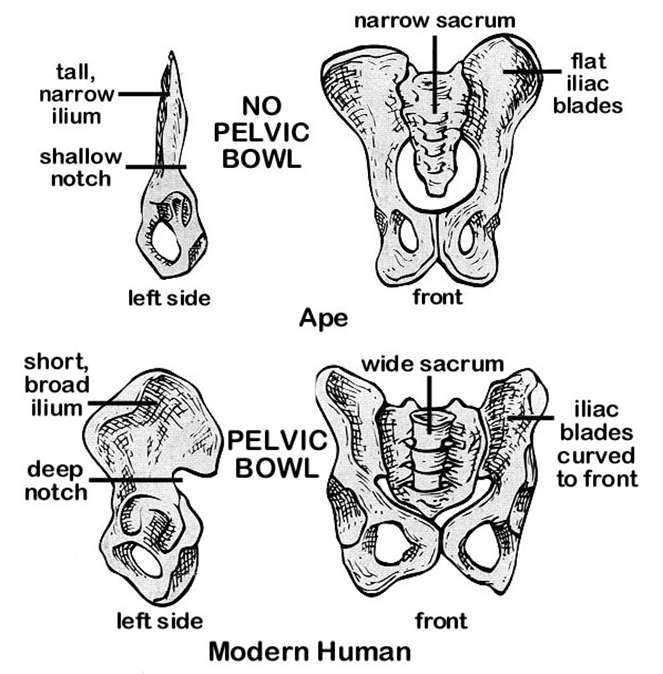

The third place to look is the pelvis. Apes have very skinny and long pelvises with flat iliac blades due to their bent over posture. Humans have very wide and short pelvises with iliac blades that flare back and outwards.

This is because we need all of that extra space to attach our stabilizing muscles for walking and running. If a fossil has a short and wide pelvis, it was most likely bipedal.

There are some exceptions to this rule, though. For instance, the giant ground sloth had a similar pelvis with wide flaring iliac blades, yet it wasn't bipedal. It's diet actually explains this. They had to spend a great deal of time standing on their legs to reach the choicest food in tall trees, hence they needed stabilizing muscles and skeletal support similar to us. I think this is one of the neatest things I've learned recently.

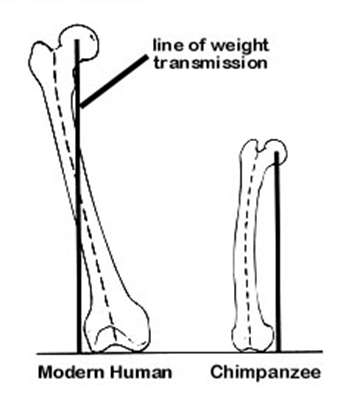

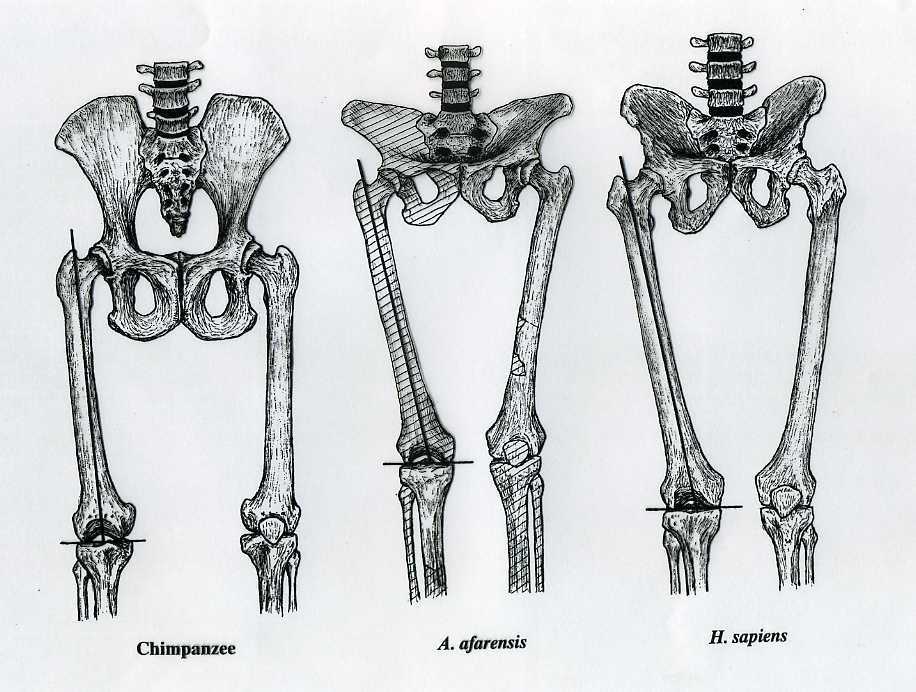

The fourth place to look is the femur. Apes have femurs that are directly beneath the pelvis, which is another reason they have a funny wobble when they try to walk bipedally. Humans have femurs that angle underneath the body to support our weight. In fact, it is VERY easy to tell whether you are dealing with a bipedal creature in this regard. All you have to do is set the knee end of the femur flat on a table. It should look something like this.

Notice how the the human femur angles inwards? If a fossil has such an inward angling femur, it was most likely bipedal. Here is a comparison of a chimp, Australopithecus, and human.

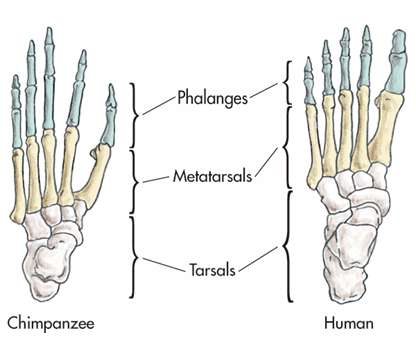

The fifth place to look is the feet. Apes have small opposable big toes and small heel bones. This is because their hand-like feet are designed for climbing and only minimal walking. Humans, on the other hand, have large non-opposable big toes and robust heel bones. This design provides for more support stepping forward onto the heel. The big toe and the other phalanges provide the "spring" needed for forward locomotion. If a fossil has a non-opposable big toe and robust heel, it was most likely bipedal.